December 12/16 - Tswalu & Home

Yellow hornbill, a visitor to the outdoor veranda of our Tswalu house

As promised in my last post, let me tell you a little about a typical day in our safari camp. However, before I continue with a typical day on safari, I’ll attempt to answer a question we’re often asked, why do we choose the particular camps that we do?

A couple of things are very important to us. For photographic needs I/we like open country, hence the number of trips we have made to the Masai Mara, the Serengeti, the Kalahari and Namibia. They all share for the most part, wide rolling plains or deserts and open country where life is lived in the open. The animals are more easily spotted in that setting but beyond that, at a purely aesthetic level, we love the landscapes, the light and the wide sweeping vistas. On the other side of the equation, most of the camps in southern South Africa are also wonderful and we spent our first safari camping in this region but there are just too many vehicles and the areas tend to be heavily treed with lots of heavy vegetation and shrubs. The animal populations in these parks are carefully protected so there are many animals to be seen and certainly lots of people enjoy them in this environment but we don’t find the experience to be very enjoyable. If you are planning to make only one or two trips to Southern Africa and your only requirement is to tick off the Big Five on your bucket list as quickly and predictably as possible, these camps are a great. But if you like to be able to watch animals interacting and to have a better window into their behaviour and their personalities and have the leisure to to do so for extended periods of time then I don’t think you can beat very large game areas in a wide sweeping landscape.

Barry, our Tswalu guide with a baby monitor lizard

In addition, we like camps that are remote or in secluded areas, where there few or no other vehicles. That allows us to have lots of time to sit and watch without constantly having to find a good observation point while many other vehicles battle for position and the air is filled with noise and diesel fumes. Lest it seem as if I’m giving the South African game experience an unfairly negative review, that’s not my intent. The couple that flew with us from the Jo’burg private air terminal to Tswalu love the southern South African camps and make 3 or 4 trips a year and all to camps where I know we would not be happy. Tswalu was their first attempt in 20 years of African game trips to get away from their normal routine. In this, as in all other areas of life, “chacun à son goût”.

The other important criteria for us at any given camp are a private vehicle of an open Land Rover type and a driver guide who will let me sit in the front jumper seat.

Pygmy falcon, he’s about 8 inches long with a wingspan of about 14 inches. The smallest raptor in Africa

Many camps use closed vehicles that look like Land Rover minibuses with closed windows. The centre section of the roof is open with a secondary roof covering the open section so that photographers need to stand up and poke their upper bodies and cameras through the open section of roof in order to take pictures, while non-photographers simply sit in their seats and look through glass-covered windows. This, for us, is a non-starter.

Stunning male Oryx

The reason for an open sided vehicle is obvious, you can’t see and smell and feel the atmosphere nor can you take take good photographs behind a pane of glass or standing up 6 or 8 feet above an animal. The downside of an open vehicle of course, is that you are fully exposed to the wind and rain. In the Serengeti we had days with winds in excess of 50 mph so after several hours it did feel as if we had been Mohammed Ali’s sparring partners and the other day here at Tswalu it was a day of biting cold winds and heavy rain so the only things that were properly covered were our cameras. But these are petty problems when compared to being sealed behind glass in a closed vehicle.

Our second requirement, a private vehicle, is probably our most important requirement. We have only ever been in a shared vehicle for two or three game drives on our first African trip and I would rather not go out than share a vehicle. Almost all camps will put 6 and sometimes 8 people in a vehicle, sometimes a few as 4, but usually at least 6. In such a populated vehicle photography is far from ideal, since you are constrained to the arc of view whose limits are set by the people around you; with a long zoom lens you need a very steady base when handholding the camera so as not to create shaky or out of focus shots, but every time someone shifts or moves, the camera and lens responds to the movement and shakes the camera and ruins your shot. Additionally, populated vehicles move frequently to mollify the passengers with the shortest attention spans.

Male Eland

Part of the joy of game drives is watching animals behave in their natural environment; watching them respond to each other and to their surroundings. We have frequently spent an hour or two sitting in one spot watching a lion pride or a coalition of cheetah brothers interact with each other or preparing to hunt. In a populated vehicle it’s simply too frustrating to have someone bouncing around in their seat complaining about wanting to move on and see something else.

My third requirement, a personal one, access to the front passenger seat, all has to do with the way I want my photographs to look. The three or four rows of seats behind the front driver and passenger seats are raised up so as to give a good view from a higher vantage point for their occupants but their downside is that the perspective of photographs taken from these seats accentuates their downward perspective. Admittedly lots of times I have had to stand on my front seat to get a shot since bushes or shrubs may have been in the way, but when I have a clear field of view I can shoot a lion or most animals at eye level. Why is this important? When I photograph animals I’m trying to create a portrait, I want to capture their character and I often like to fill the frame with their face or their profile. I don’t know many interesting portraits that are taken with the sitter’s head below the level of the lens, showing the top of the sitter’s head from above. I’m not always successful in doing this but it’s important for me to try. I want to create the conditions for me to respond to the animal as an individual with their own sense of self and life and emotions in their eyes as I look directly into their eyes.

Spotted eagle owl

Wow, I started to tell you about a day in a safari camp and I’ve moved into my personal wildlife photography manifesto! Sorry, won’t happen again!

By the way, I’m finishing the writing of this post at home, having arrived last night after 36 hours in transit, 18 hours in the air on 3 flights from Tswalu to Toronto and 18 hours in airports awaiting next flights. A very long day only to discover on arrival in Toronto, while collecting our checked luggage, that V’s suitcase was sans lock, the suitcases straps were undone and her bag’s zipper was open about 6 inches. On arriving home, when she opened her bag to examine the contents for missing items and expecting the worst, she discovered that a large ziplock bag, weighing about a kilo and filled with red Kalahari sand was missing. As an aside we have many bags of sand from around the world, V’s determination to collect sand is representative of the larger question, why do some people have the urgency to collect curious and seemingly mundane items? It’s a question worthy of further study.

A behaviour we’d never seen before. A meerkat at the top of a 6 foot acacia tree, scouting for birds of prey.

In any event, the sand in its bag was found at the bottom of her suitcase along with the lock. I can only surmise that when her bag was x-rayed, the security folks must have thought that they had hit the mother lode of drug smuggling and therefore had been very disappointed to discover only sand, to the point that they simply threw the sand back into the bag along with the lock and didn’t bother to restrap it or rezip it properly. Behind every silver lining there is a dark cloud and some security officer’s hopes for promotion and a great Xmas bonus had been ruined, not a good day for him or her but a wonderful day for us!

But back to a typical safari day. So what is a day in camp actually like? Depending on the time of sunrise and sunset and the time of year the schedules may vary but the overall structure is reasonably similar among all the various camps at which we have stayed over the years.

Male Southern Masked Weaver building a nest for his mate

Each day requires some preliminary preparation the previous evening. All camera batteries need to be charged, images downloaded from camera cards to the computer, and all camera equipment cleaned, readied and packed in their carrying case for the following morning. With the advent of the iPhone, this too needs to be charged; it can be very useful for emergency videos and shots.

Our next day’s clothing needs to be organized and at hand, fumbling half-asleep in the dark does not make for a great start to the day, particularly when you’re putting on clothes, not shedding them.

Because the sunrise on the Serengeti was about 6am our wake-up call was at 5:30am and we were washed, dressed and loaded in our vehicle and on the trail by 6am. Here at Tswalu, much farther south, the sunrise is at about 5’ish so our wake-up call is at 4:30 and we’re in our vehicle and off by 5am. We can manage to brush our teeth, wash, and dress by about 4:50 which gives us ten minutes to grab a latte and a freshly baked croissant at the lodge to take in our vehicle as we begin our morning’s photo hunt. The kitchen is up very early and has prepared the croissants, snacks and fresh orange juice but we’re happy with a croissant and coffee.

So, climbing into our carefully curated vehicle, we start our day, cameras at the ready. The guide driver and the tracker are extremely knowledgeable and watching them read signs and tracks as they try and locate an animal is an education. They seem to know every bird and can tell you about the plants, flowers, insects, animals, ecology and geology of the region and the behaviour of all the life around them, endlessly fascinating.

Sociable weavers’ nests. They can be massive and are the home to dozens of familes. You often see them of such a size that branches or whole trees are unable to bear their weight and fall.

But we are not mere passengers along for the ride. V and I are constantly aware that in order to fully enjoy the experience we need to be active participants. You can be a passive watcher but you cannot be a passive seer. Animals and birds come in a host of sizes and shapes and colours and their environment can be brushy, grassy, sandy, rocky or treed and it is always filled with light and shadows. Looking for patterns, things that don’t quite fit, things that shouldn’t be there or things should be there and aren’t, these are all part of the process of active seeing and the joy of the process is spotting something that has heretofore eluded the eye and finding a picture where none had existed a moment before. This is not to suggest that we are even slightly good at this, we simply don’t know enough and have not experienced enough to be able to make sense of everything that we see and what it’s telling us, but It’s fascinating to try.

We are looking for animals and birds to photograph, to see and capture something that we have never seen before and which gives us an insight into an animal or bird that helps lift them off the page of the bird book or the animal guide and makes them partners with us in a world we all share and are trying to come to terms with. We can never understand what it must feel like to be who they are and face what they face but it’s the closest way that I know of to appreciate the fact that they are fully alive, not scientific definitions or the subjects of a television documentary, and that sometimes allows us to make a single, brief, tenuous connection.

One other important requirement that we always ask camps for is that they assign us a driver who is him or herself a photographer. Driving a vehicle for a photographer is a very subtle art, there is a lot more to it than simply finding an animal to photograph. As difficult as the finding can sometimes be, it’s only the beginning of the process. The driver needs to try and stay downwind of the animal, certainly during the tracking process, so as not to prematurely warn of our presence and make the animal wary or cause it to bolt. The driver needs to be aware of the sun’s position in relation to the animal, needs to line the vehicle up while the animal is resting or moving so that the photographer is in an ideal shooting line and needs to understand animal behaviour so as to anticipate what it’s likely to do next and where the ideal next position needs to be to ensure a clear shot. Light and shadows, wind direction, the sun’s position and intervening obstacles constantly change and need to be taken into consideration to make for a clear, open, properly-oriented shot. Our two guides on this trip, exceptional photographers in their own right, were superb and I think the best we have ever had. Hats off to you both, Dula and Barry. Should any of my readers ever want to try a trip to one of these camps be sure to ask for Dula in Namiri Plains and Barry at Tswalu, cannot recommend them highly enough.

A mother Bat Eared Fox and her kit. They were about 50 metres away and the camera is doing a wonderful job of focusing on the grass, not on the animals!

I’m often asked why we keep going back, haven’t we already seen lots of lions? Yes we have but we keep going back, not to collect yet another lion shot, but to experience and capture images that show interactions or moments of intimacy or those rare moments that allow V and I to share our own wonder at lives so different from ours but, in some very real way so similar as well. For example, in Tswalu we stayed with a pair of mating lions for a significant length of time. We have had this opportunity once before but that first time the mating pair were surrounded by 5 or 6 vehicles each filled with 7 or 8 people who were loudly enjoying the spectacle, it felt somewhat creepy so we left.

In this instance, the mating pair were both out in the open, resting on the red sand of the road, with no other vehicles in sight. Previously unknown to us was the fact that while the female is in estrus, a period of up to a week, her chosen partner mates with her about 6 times an hour, day and most of the night for the entire 6 or 7 day period. The mating act itself only consumes 20 or 30 seconds but is violent and can be bloody. By common consent, we couldn’t see if it was the male or the female that initiated the encounter, the male would mount the female and hold himself in position on his haunches and by grabbing the back of her neck in his jaws. The female’s neck exhibited many fresh, bloody bite marks and the male for his part had wounds on his forearms for, when they decouple, there is a savage exchange of snarls and bites, no quiet post-coral cigarettes here. We stayed for a number of cycles and were exhausted watching, the amount of energy expended was enormous. I assume that the process ensured that they met an evolutionary criterion, those animals who were not strong and vigorous enough and without the endurance required to meet these extraordinary demands would not the be able to pass on their genes. It’s the privilege of being able to experience these moments that keeps bringing us back.

During mating

After mating

But back to the mundane, we continue our exploration, existential and photographic until about 9:30 or 10 and then head back to our camp for breakfast. The food at Tswalu is excellent and our daily struggle is to keep appetite in check so that we won’t need two seats each on the plane home in which to squeeze our overfed bodies.

We have our afternoon in which to download and work on photographs, write blogs, shower and clean up, and catch up on sleep. Added to that on this trip is the necessity for Christmas shopping on-line in hopes that everything will be delivered by the time we return, a week before Christmas.

At 4pm we’re back on our vehicle for a game drive that will end around 7:30pm and our return drive to the lodge in the dark. Time for a beer and then a very good dinner and glass of wine and into bed by 9:30 after having prepared for the following day’s expedition.

With some diversions along the way, that’s how we spend a day in camp, and now that we’re back home and catching up on sleep and rest, I’m already thinking of how and when we’ll be back.

After Note:

Cheetah boys now.

One of the more special parts of our trip occurred at Tswalu. We have always loved cheetah and seeing them in their natural habitat was one of the original drivers for our first trip to Africa in 2012. At that time, during our first visit to Tswalu, we were lucky enough to spend time, over a couple of days, with a pair of cheetah brothers who were then 2 years old and hunting on their own.

You should know that it is quite usual for brothers, both from the same litter and across litters, to come together and form coalitions which provide more security, cheetahs are after all the prey of lions, leopards and hyenas, as well as significantly improving their hunting capability. These coalitions can be very long lasting, life-long in many cases. I’m sure a few of my readers will remember our last trip to Kenya and the Masai Mara in 2018 when we followed, at times with a BBC film crew, a coalition of 5 brothers who hunted in the Mara as well as across the border into Tanzania. They were very well-known, hence the film crew, and were the offspring of a very famous mother, Malika, who I also wrote about at that time. She was an extremely capable, very intelligent cat who, unusually, survived after being left as an orphan and grew up into cheetah with a very strong personality and character. We had seen her on earlier trips to the Mara and I had the very sad honour of having taken her last photo. Shortly after we last saw her, it turned out to be a couple of hours before she died, I was able to get a shot of her. She was last seen attempting to cross a river swollen by a heavy downpour and was washed away. She was never found. Both V and I were very upset when we got the news; such is the hold that cheetah have on those of us who admire them.

Cheetah boys 10 years ago.

But back to my story. The two cheetah boys at Tswalu were still holding their own and it was an emotional reconnection to see and spend time with them after 10 years. Cheetah, with extraordinary luck, can survive in the wild for up to 14 years and our two boys who at that age were still capable of hunting and surviving, but were showing their age. We know that if anything happens to one, the other one will be unable to survive on his own so it too was a sad farewell when we left. Our last visit with them was in the sunset of our last game drive. We stopped our vehicle to watch them and then Barry our guide asked if I’d like to get out of the vehicle and try and get a closeup, and so we did. They let us approach to about 3 metres and my last shot of the trip is of our two brothers, washed in the red glow of the setting sun.

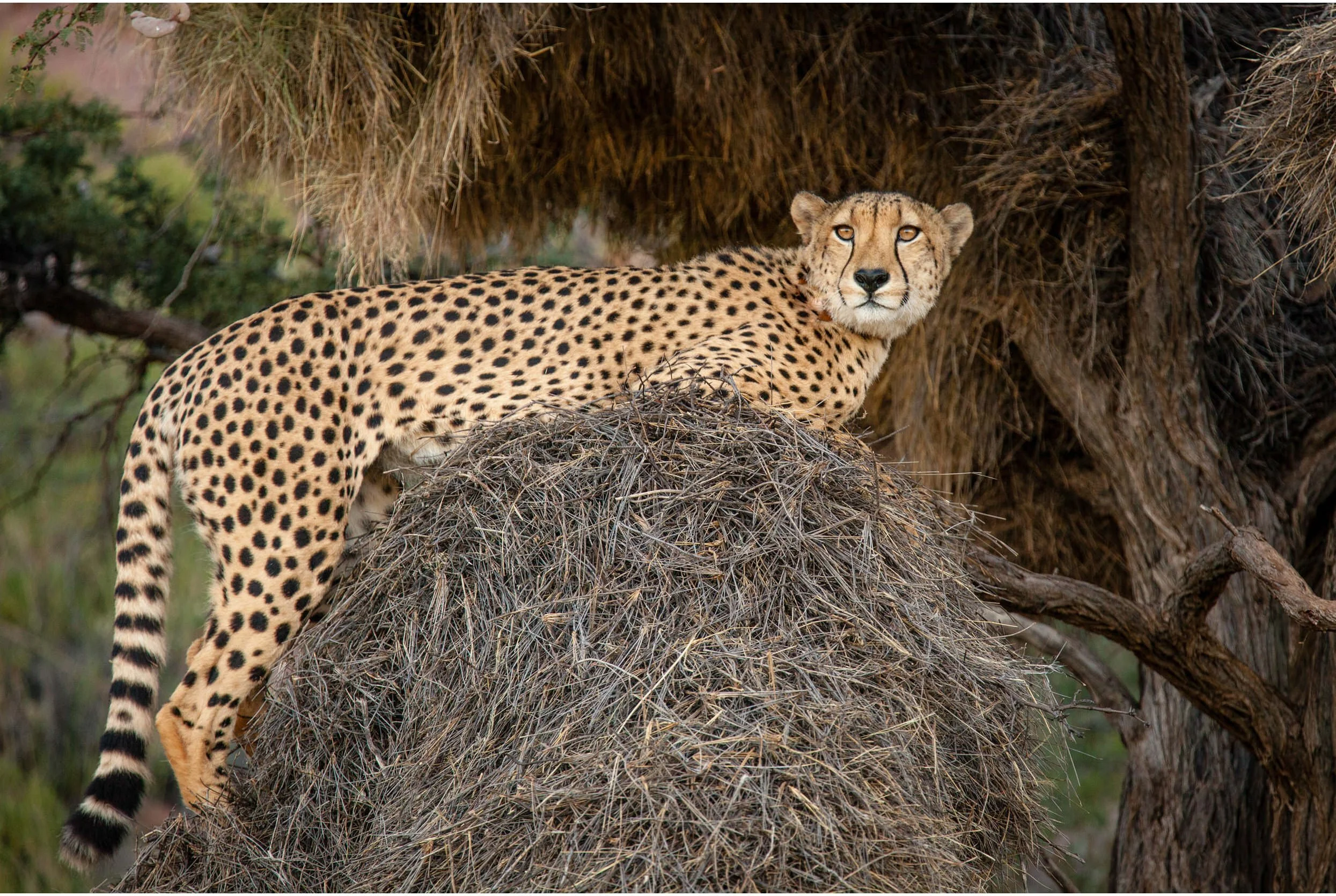

Cheetahs don’t climb trees but this is one of the two cheetah boys from 10 years ago on a sociable weavers nest

Final fun note, a lagniappe, we discovered two new terms for groups of particular animals. A group of rhinos is called a “crash” and a group of giraffes is called a “kaleidoscope”.

More to come!

Farewell to Tswalu and to Africa